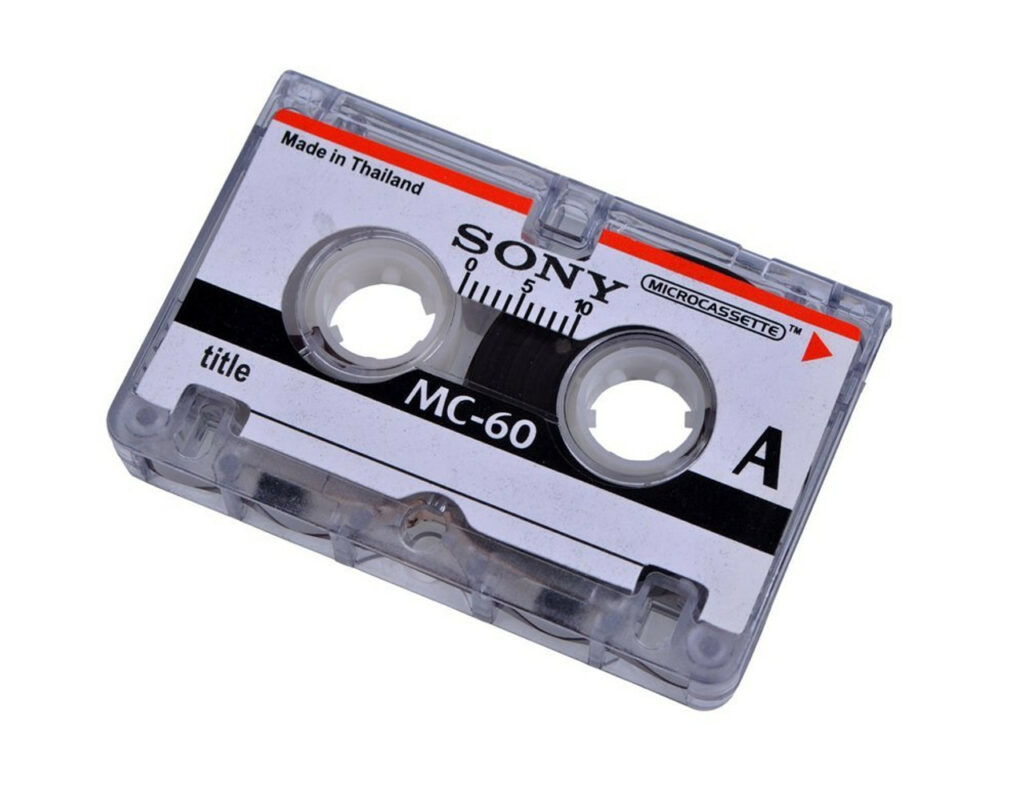

The microcassette was introduced in 1969 by Olympus, as a conveniently sized alternative to the standard compact cassette we all know and love. The word “alternative” must be used loosely, however, as the microcassette is sonically inferior to the compact cassette in every way. The tiny (albeit convenient) housing only holds a small amount of tape, and to compensate, the tape is thinner, and the speed is slowed down drastically (50-75%) from that of a normal cassette. Slower tape speed means lower fidelity, and given that 99% of microcassettes were used in hand-held dictation recorders or telephone answering machines, they are really only suitable for low-fidelity voice recordings.

That being said, there are many microcassettes which contain important interviews, family heirloom recordings, and other material that should be preserved by digitization. The transfer procedure is not as straightforward as with hi-fi tape formats, since the playback machines themselves are not compatible with most studio gear. Various adapters can make the job doable, but it can still be a challenge to retrieve decent audio. Usually rife with clicks, handling noise and background sound magnified by an “automatic level” setting, even the best-recorded microcassettes usually do not sound very good on their own.

But once in the initial transfer has been made, audio engineers now have software options that allow us to remove unwanted noise and enhance poor fidelity better than ever before. Most of the common anomalies can be greatly improved, and sometimes removed altogether.

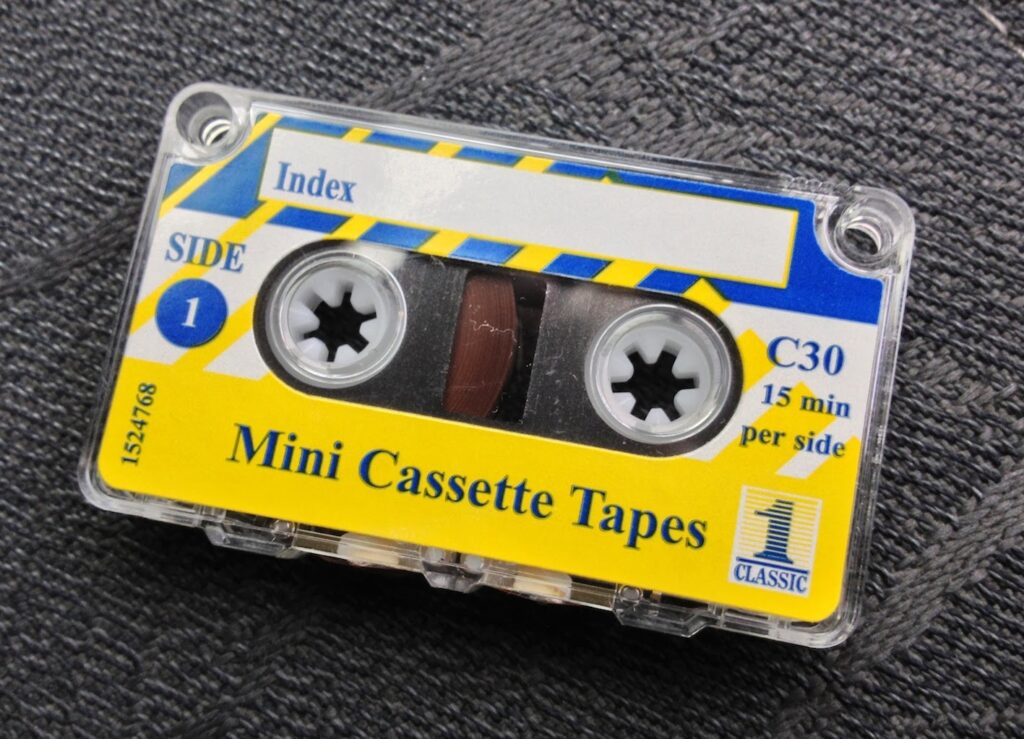

Remember the format war between VHS and Beta videotapes? Or the later war between Blu-ray and HD DVD? Well, the mini-cassette has a similar story. Developed in 1967 by Philips, it is similar in size and performance to the microcassette, but they are not compatible. Different machines must be used to play each one. And because microcassettes won the war, the tapes are scarce, and machines to play them even scarcer. But we can do it!