Many people have never seen a cylinder record. Commercially released ones were made from the 1890s up through 1929, eventually giving way to the disc records that everyone knows. The earliest cylinders (made up through 1912) are made of wax and are quite fragile. The later ones are made of celluloid and are somewhat more robust. Nevertheless, the format proved to be too inconvenient to survive, and when Edison’s phonograph works folded in 1929, the cylinder went with it.

Nowadays people sometimes come across collections of cylinders and would like to be able to play them. One solution is to buy a working antique machine. The original cylinder phonographs were very well made, and there are still thousands of Edison Phonographs and Columbia Graphophones in existence. However, there are a few caveats with this solution, and unless you know what you’re doing you can quickly ruin your records.

Firstly, there are two-minute and four-minute records which can look the same to the untrained eye. Early machines were designed to play one or the other, or in some cases had a “combination reproducer” that could be adjusted to play both. The caveat? Playing a record with the wrong reproducer can ruin it in a single play.

The earlier 2-minute wax cylinders exist in both black wax and various shades of brown. This is where extreme caution must be exercised. The brown wax (often dating back to the 1890s) is much softer and more fragile and must be played with an earlier style light weight reproducer (the “automatic”). Using the standard reproducer meant for black wax (e.g. the common Edison Type C) will quickly wear the grooves down. Just finding one of the earlier reproducers can be an issue, and they often cost more than the phonograph they fit. The condition of the sapphire stylus is also a concern. If it is chipped or worn, it can damage your records as well.

Another concern is cylinders that have developed mold on their surface from years of humidity. Our first instinct of course would be to clean off the mold— but DO NOT DO THIS! The mold has actually “eaten into” the wax and may represent the only remaining playable surface. Unless you really know what you’re doing, do not try to clean cylinders at all.

Sometimes cylinders can become misshapen. Out-of-round, warped records are common, and the later celluloid records (Edison Blue Amberol, U.S. Everlasting, Columbia 2-minute Indestructible) can be prone to shrinkage over time. This means the groove width has become slightly narrower, and playback on an antique machine may cause skips and tracking problems since the feed screw was designed for very specific tolerances that have now changed.

In addition to the standard sized records (2.25 inches in diameter) there are other formats used by Edison and Pathe with a larger diameter. These require totally different difficult-to-find machines for playback.

So, how to go about transferring and preserving this precious audio?

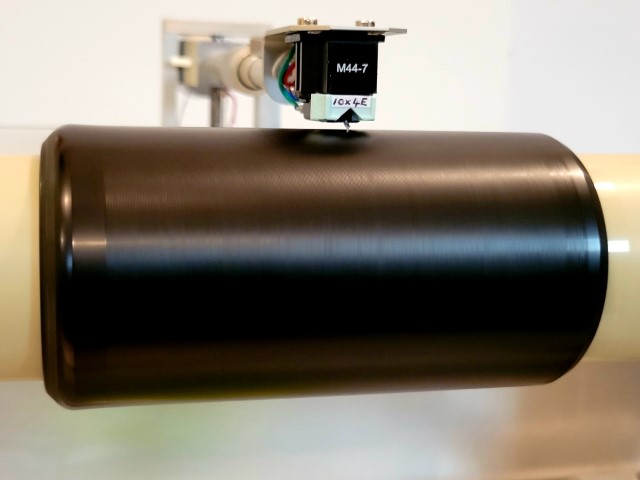

Several decades ago, devices were created to allow electric playback of cylinder records. They involved replacing the Edison reproducer with a specially mounted modern phono cartridge, still using the wind-up spring motor and belt-driven mandrel of an antique phonograph. Though this allowed for better transfer of the audio (as opposed to the old school method of sticking a microphone in the playback horn) it left several problems in place, such as the grinding noise of the motor being picked up by the cartridge and the wobble associated with cylinders that were no longer perfectly round after sitting for a century. Playing all the records with the same size stylus was also not ideal, as some records respond better with different sizes and shapes of diamonds/sapphires. More recently, dedicated laboratory machines emerged, such as the French-made Archéophone, which solves all of the above problems and provides accurate transfers. This is what we use at Commodore.