In Defense of the Lowly Compact Disc!

I’m always a bit nonplussed when I hear people say that nobody listens to CD’s anymore. While it is true that the format is no longer the latest and greatest, and that devices to play the discs are becoming scarce (in fact no longer even an option on new vehicles) the compact disc is still truly relevant, and in many ways superior to its conveniently downloadable mp3 offspring.

In terms of sheer audio quality, the CD is indeed ’80s technology. With its primitive 44.1kHz 16-bit specs, we are in fact listening to audio that only uses 44,100 samples per-second instead of the 192,000 or even 384,000 samples available in current high-definition systems. I’m sure the average human ear could tell the difference immediately. (That was sarcasm.) Additionally, the CD bitrate only allows for 65,536 levels of volume, rather than the millions of levels available in 24 and 32-bit systems. Again, a glaring audible difference to the average ear, I am sure. (Also sarcasm.) But it is important to remember that the mp3s we download have been dumbed down to this same 44/16 spec, and additionally fiddled with to allow them to exist in a fraction of the storage space of uncompressed CD audio. Mp3 audio, by its very nature, is inferior to the ’80s technology of compact discs. This is not to say that mp3s don’t sound good; well-made ones are often nearly indistinguishable from their uncompressed counterparts. So when you hear someone complaining about how mp3’s “filter out all the highs and lows” and other such claims, they are probably referring to that 4-bit voice that said “…you’ve got mail…” on the earliest incarnations of AOL, or the inferior sound of most streamed music. Nevertheless, the music most people now listen to is below CD-quality.

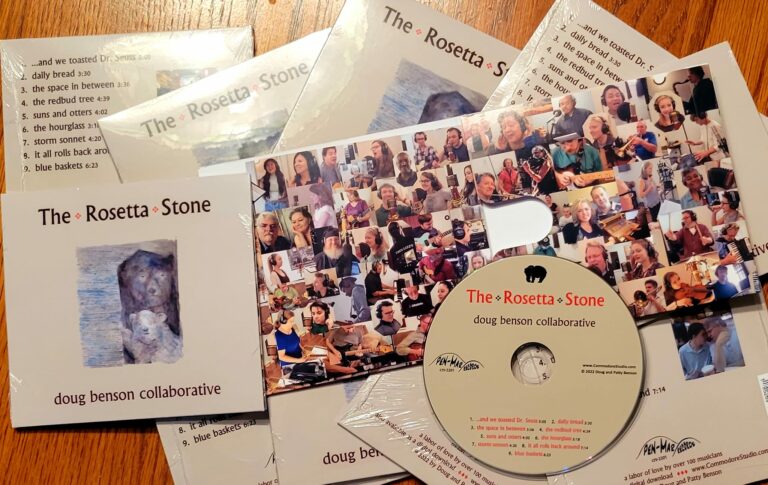

That being said, there are other things to consider. The aesthetic and informational value of the CD packaging has long been an important part of the product. The glory days of vinyl gave us at least two square feet of real estate for artwork and credits (sometimes even lyrics) and made the enjoyment of music a visual and tactile delight as well as an aural one. With the advent of CD’s, the real estate shrank considerably, but still allowed some space to list production credits, publisher information and lyrics, in addition to the miniaturized artwork that would help to define the product. Now we are lucky if a downloaded mp3 includes a one square-inch blurry image of the cover, much less any information about the album. Many listeners still want to feel like they are buying something tangible that can’t be wiped off their device when Big Brother decides it shouldn’t be there. (Yes, that’s a reference to a particular recent global event with Apple devices.) Mp3’s seem a little too “virtual” and temporary for some tastes. Including my own.

From the perspective of an artist, the CD also adds a real legitimacy to a release. It’s something they can put in the hand of a fan, an agent or a reviewer, rather than a flimsy download card, or even worse, saying “just download my digital-only album.” Tangibility is still important.

I also lament the demise of the car CD player. Many online pundits smugly tell us Luddites to “…just rip your old CD’s to mp3s on your computer so you can play them in your car.” Keep in mind that most new computers don’t have a CD drive anymore, so even that option is disappearing. Plus, if I have just purchased a CD, whether it be from a store or an artist’s merchandise table at a concert, I don’t want to have to wait until I get home and rip the CD to an mp3 on my computer (if I am even able to) before I can listen to the music I just bought! There are also some nasty brand wars playing out; for example, the most recent Toyota vehicles will only pair with Apple phones.

Now, here’s the real rub: the more industrial side of the music industry would love to eliminate physical formats altogether. There are a couple of reasons for this. First, it would eliminate their need for manufacturing, warehouse, and shipping costs; AND the little virtual bits of data cost them nothing, but still cost the consumer the same as the beautiful physical albums we used to buy. Win-win for the industry. But wait, there’s more! Everyone’s personal music is stored in a “cloud” (which is really just someone else’s computer) and accessed through an account of some sort, and it’s sometimes difficult or impossible to move one’s library between devices as playback hardware becomes obsolete every few years. So, the consumer must often re-purchase music that they already paid for in order to keep listening to it. For example, recent changes in the Amazon Kindle Fire now make it nearly impossible to add any music that was not purchased through Amazon.

So as time and technology march on, some things are made worse instead of better. The demise of the tangible audio product is reminiscent of a restless husband in mid-life crisis; throwing away something of quality in exchange for something fleeting; and only later realizing that what he had was so much better.